The history of Aleksi 21

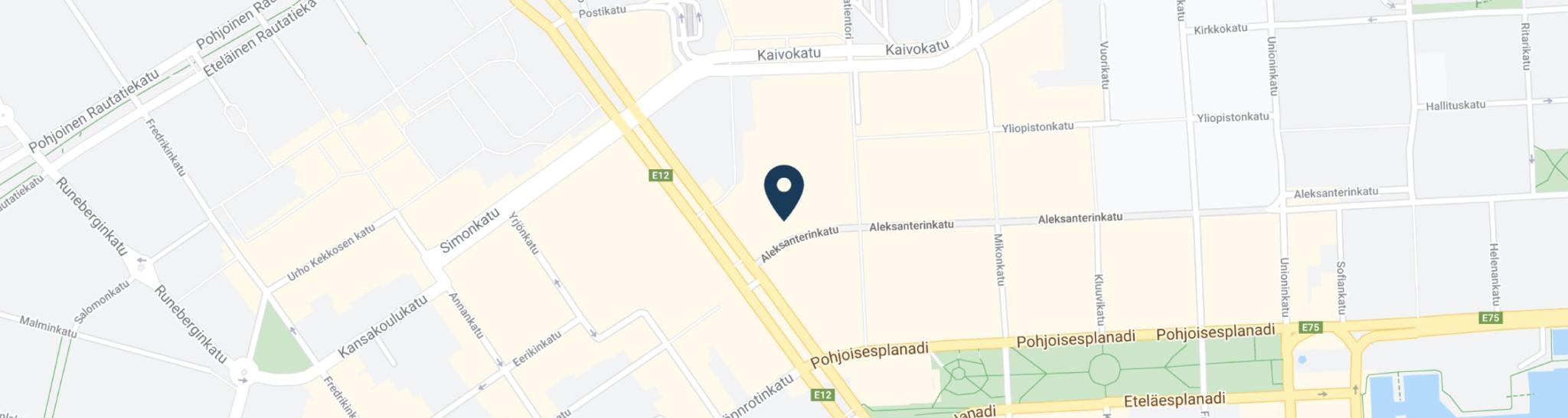

The western end of Aleksanterinkatu started to find its shape in the 1830s when the drying of the gloe lake – a bay that was closed up – was initiated, and the master plan created by Johan Albrecht Ehrenström was expanded. Architect, Intendant Carl Ludvig Engel created the plans for the new street and block division in 1837–38. Block 96 became fairly large in comparison to the traditional rectangular block structure of the city. This was because Läntinen and Itäinen Heikinkatu, running diagonally in relation to the city centre’s street network, were located along its sides. The block had a corner cut off because of the small square surrounding the Kluuvi well. Aleksanterikatu had already grown into the most important business street of the city. Now, connecting Aleksanterinkatu to the western exit route increased the value along it even further. The sales of the new plot started immediately, and the first buildings in the area were completed in the early 1840s. A majority of the buildings were made of wood, which was probably because of the wet history of the area as a gloe lake and swamp.

Master Smith L. F. Graeffe bought the Aleksanterinkatu 21 plot from the City of Helsinki in 1845. Already the same year, the blueprints were finished for building the plot. Initially, Graeffe ordered only the construction of one building, a smaller residential building located along the street. In 1860, the larger residential building and yard buildings were completed according to the original blueprints. The building along the street was made of square pine and spruce timber. It had eight rooms equipped with tile stoves and French wallpaper, two heated foyers, two kitchens, two storage rooms and two outdoor verandas. The roof was made of sheet metal. At the time, the building was unlined.

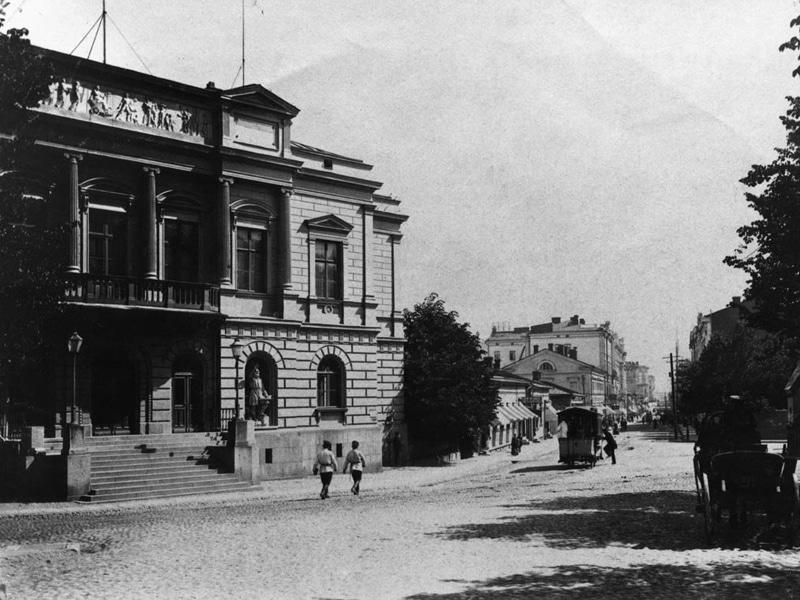

In 1897, Julius Tallberg purchased the Aleksanterinkatu 21 property from the heirs of Graeffe. After gaining control of the Aleksanterinkatu 21 plot, Tallberg asked his former business associate and friend, master builder Elia Heikel to draw new blueprints. The facade was designed by Stefan Michailow from the City of Turku. In the archives of the Julius Tallberg Corporation, there is an old sepia-toned photograph of a building that from the outside looks like the newly finished business palace of Aleksanterinkatu. But if you look closer, you can see that the building is not in Finland. The text behind the photo says it was taken in Glasgow, Scotland. How Julius Tallberg got hold of the photo remains a mystery.

The architecture of the building’s facade is based on large street-level shop windows. This creates the impression that the four upper floors of the building are floating on the lightweight glass screens. This was a novelty in Finnish architecture at the turn of the century, and classically trained architects couldn’t understand ideas based on the internal structure of the building.

Visually, the three middle floors are controlled by the strongly plastic arcade that ends in rich relief decorations. Apparently, Julius Tallberg ordered the decorative sculptures from his friend Robert Stigell. The repeated relief themes are Forging and the Art of Construction, as well as Seafaring and Agriculture. In 1888, Stigell sculpted the statues of Ilmarinen and Väinämöinen, characters in the Finnish national epic Kalevala, by the Student House’s entrance. These statues, like those of the Tallberg building, were cast from concrete. Stigell also used allegorical characters on another building on Aleksanterinkatu, the Lundqvist business building at Aleksanterinkatu 13 completed in 1901. There, the themes depicted in the sculptures are Spinning thread and Hunting. The muscly Atlases of the insurance company Kaleva’s building from 1889 along Erottajankatu were also sculpted by Stigell.

Elia Heikel and the new construction technique

Elia Heikel’s important investment helped execute the structurally challenging floor with shop windows and business space with no partition walls. In the Aleksanterinkatu 21 building, Heikel was consistent in his use of iron structures. By the shop windows, he reinforced the structures with double iron pillars. According to the explanations of the blueprints, the facades of the upper floors were reinforced with steel structures and ferro-concrete. Heikel constructed the pillars of steel rails and flanged beams, riveting them into cross-like pillars.

In 1915, Architect Selim A. Lindqvist drew plans for the addition of four more floors to the yard wings. At the same time, a layer of plaster boards was added to the insulation of the framework’s uppermost floor on the Aleksanterinkatu side. In connection with the elevation, detailed calculations were made of the load-bearing capacity of the existing structural parts.

For instance, in the spring of 1945, a curved stairway was built between the first and second floors of the main building on Aleksanterinkatu. The stairs were demolished in 1974. In addition, the shop windows and entrances on Aleksanterinkatu were renewed in 1945.

Renovating the block as the City block

In 1958, the owners of all five old properties with a connection to Citykäytävä commissioned Architect Viljo Revell to develop the old business block. In the early phase, the plan included three plots, while Aleksanterinkatu 21 had to wait its turn. In the early 1970s, Architect Office Viljo Revell and Heikki Castrén, later Castrén – Jauhiainen – Nuutila, created some alteration plans for the plot, but the actual renovation work didn’t start until the early 1980s. The most visible change in the 1980s renovation was the glass ceiling of the Aleksanterinkatu 21 courtyard.

The building today

The plot has an office and retail building with five floors above ground and four underground. In all, the building gained its current look in 1910 when the city corridor passing through the building was opened. However, the building has been expanded and changed in several renovations.

Large alteration work on the building recently came to an end. The purpose was to create more business space. The latest, very important addition was that the property was connected to the city centre service tunnel. This has transferred all service traffic underground. The facade of the upper floors was reinforced with steel structures and ferro-concrete. The building is in the district heating network, and all spaces have mechanical ventilation and cooling. All building technology systems were renewed in connection with the alteration work.